I don’t know how to write dialogue!

However…

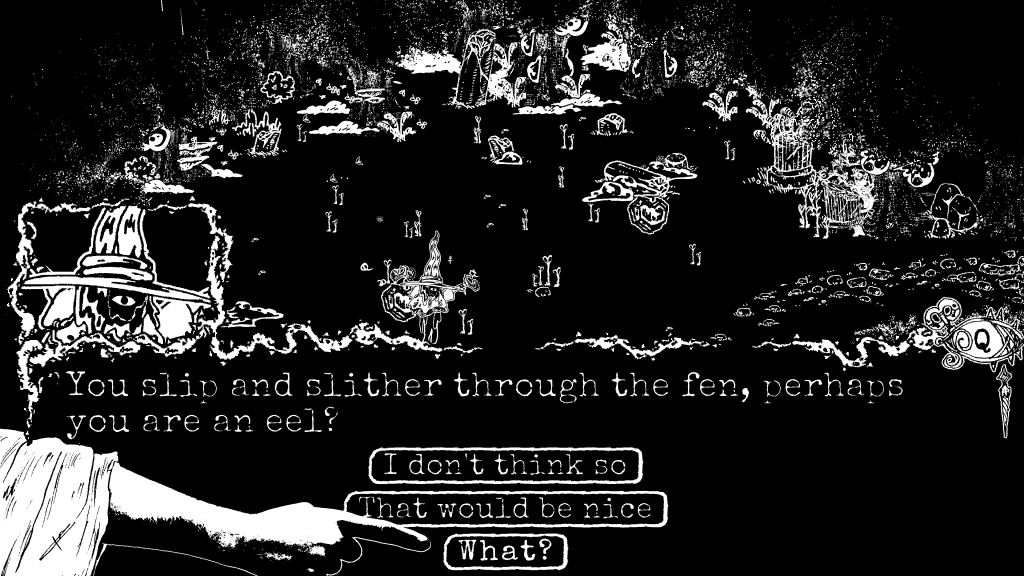

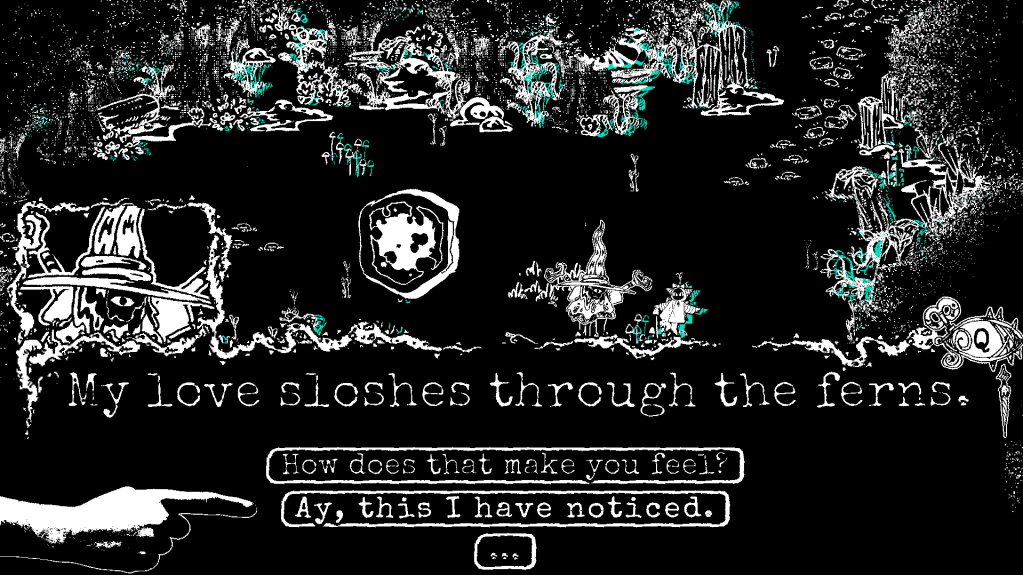

Part of my job now involves writing dialogue for the game Key Fairy.

This is a concern.

…

To avoid falling into one of the numerous traps that plague novice games writers, I have tried to enforce a series of Rules and Goals for my writing.

The aim is to treat writing as a Design Problem, with strong Limitations guiding the process towards a clear and cohesive voice!

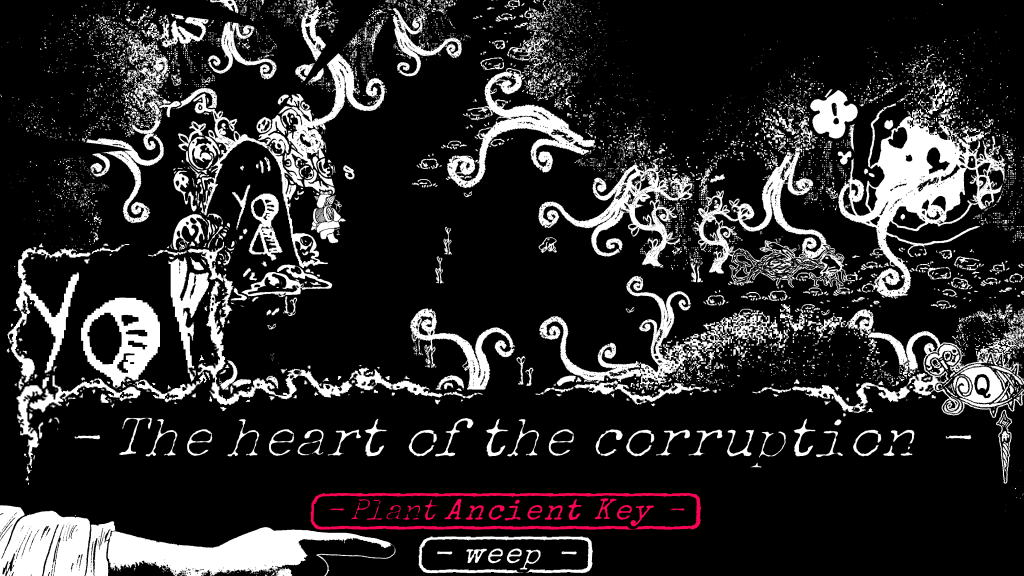

What’s the Vibe?

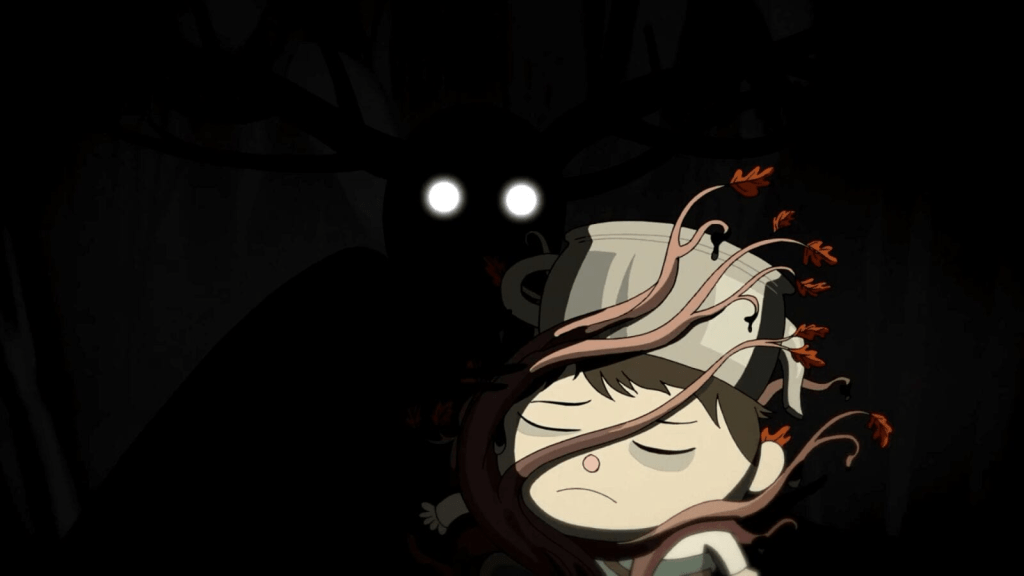

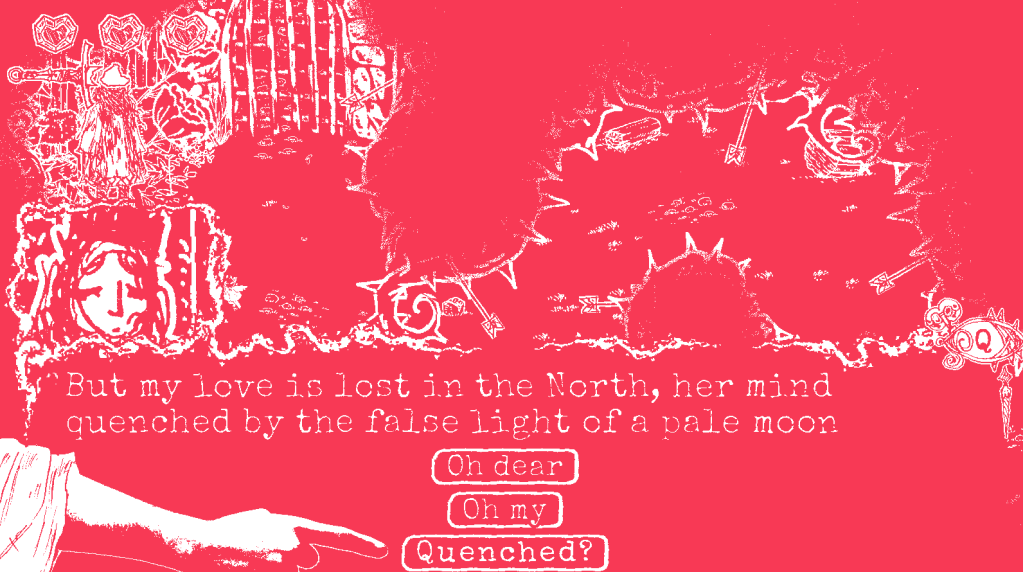

We want the game to have a Folkloric Atmosphere, that exists at the intersection of Spooky and Whimsical.

Core Goals

Goal 0: Rhythm

Old folklore has a rhythm to the prose.

It’s not quite poetry, but it is poetry adjacent.

And I want the dialogue to capture that experience.

Rhythm.

With player choices being part of it.

Producing a sing-song back-and-forth between the Fairly Folk of the Forest.

Goal 1: Dialogue Shouldn’t be a CHORE!

Games Don’t Need Dialogue!

So if it’s going to be there, it should be fun, and engaging, and interesting.

I want the dialogue to be Short!

I want the interaction to feel Crunchy!

And I want the writing to be Unique!

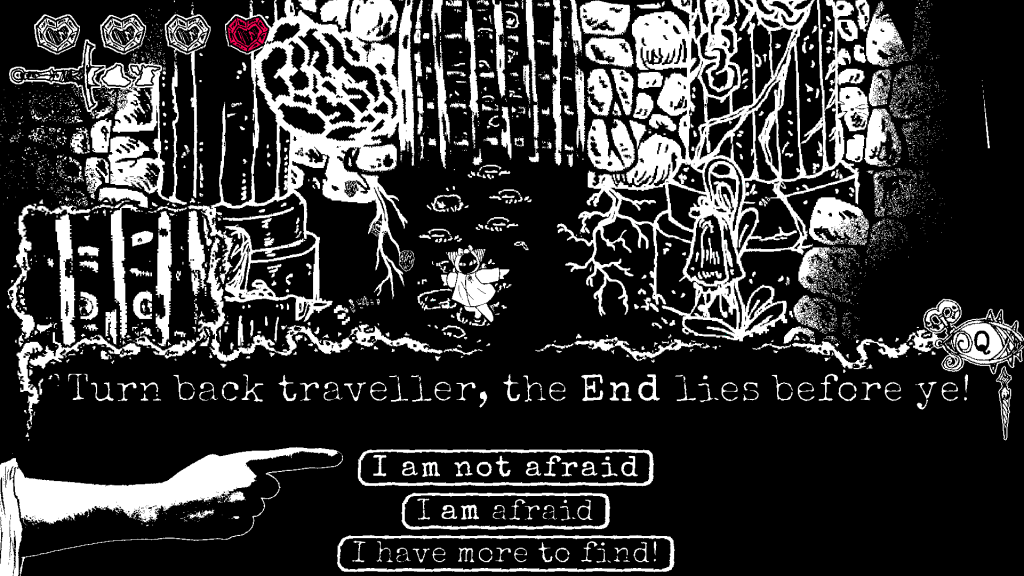

Goal 2: Agency over Character, not Narrative.

I want the dialogue choices to feel Meaningful.

BUT!

This is not a choose-your-own-adventure game.

There is no branching narrative.

Instead, dialogue choices should allow the player to define how they are expressing themselves in the conversation.

Are you scared? Are you brave? Are you cheeky? Are you lost? Are you strong-headed?

I’m drawing a lot of inspiration from folkloric storytelling practice in how much agency the character is given over the narrative (for more on this, see this other thing I wrote).

We want the key fairy to be a part of the story, with their personality and character a shared performance between us (the designers) and you (the player).

You can decide to be brave, but you can’t decide to be a classical hero. You can decide to be cheeky, but you can’t decide to attack the monsters.

The key fairy is a pacifist.

They are a small creature in a big forest.

They scurry, and cry, and save the world.

Note: If you think this is bad, and that this is a bad way to provide player agency, and that I should be sad and ashamed of myself and kicked out of the games industry for being a worm, I am happy to fight you in a parking lot of your choosing.

Goal 3: Humorous, Esoteric, Informational.

The dialogue should ideally be a pretty even mix of Humorous, Esoteric, and Informational.

Humour helps build a playful, whimsical, atmosphere, and it helps players lower their guard for the more emotional or melancholy elements of the game

As the game progresses the “humour” tap is slowly tightened.

Esoteric writing adds mystery, confusion and a sense of uneasy surreality to the world.

We want you to feel lost, and confused.

Secrets built upon secrets.

Informational dialogue is important because it’s one of the few ways players are actually going to get information.

We don’t provide a map or quest tracking system, so if you want to know where to go, or what you need, you have to talk to people.

This, in turn, encourages players to actually engage with the dialogue, for you never know which character will have a useful bit of information!

HARD RULES!

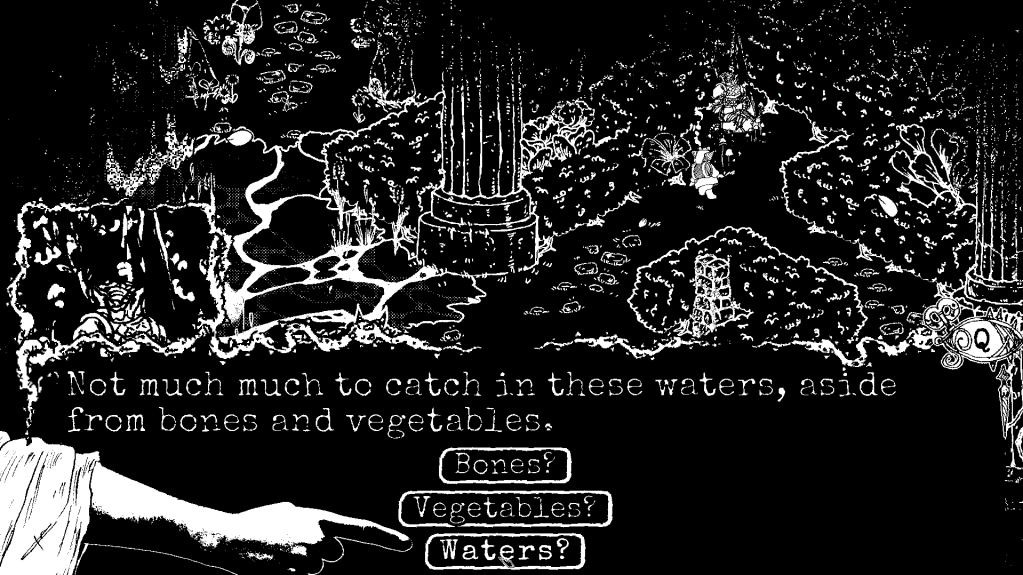

Rule 1: Fit in the box!

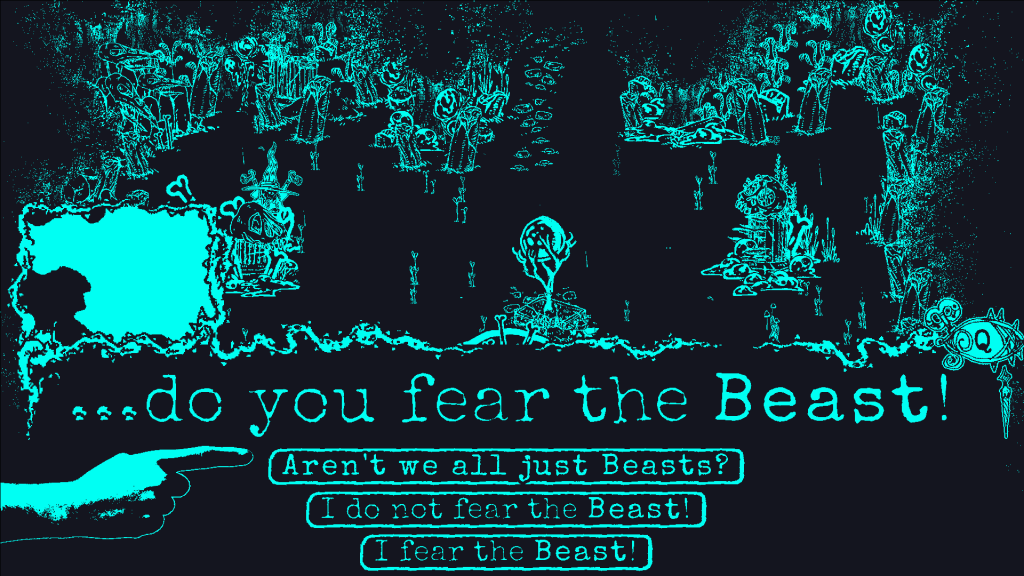

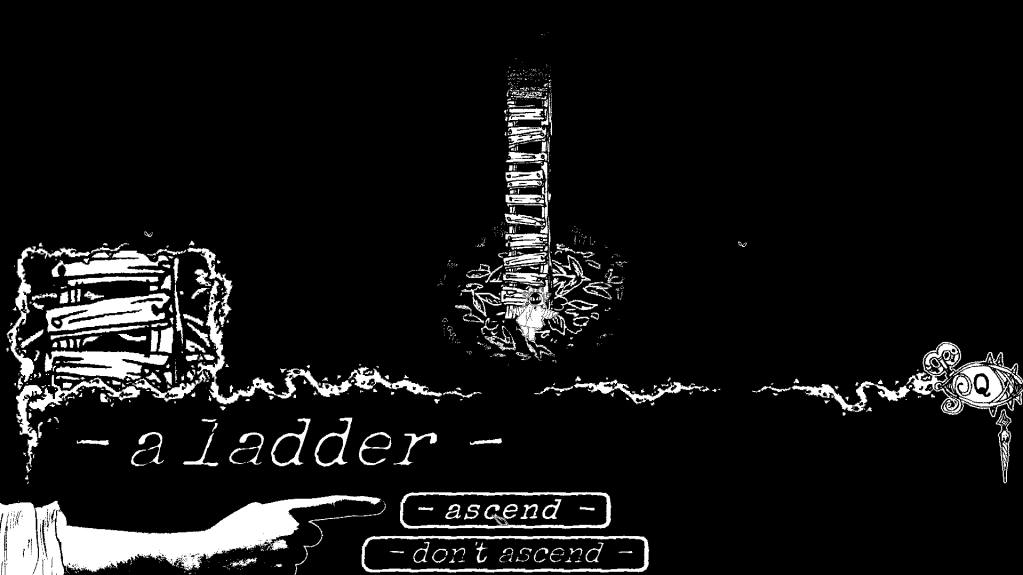

When designing the dialogue system, I specifically gave the monsters a tiny dialogue box.

This prevents long monologues without player interaction, and forces me to be CONCISE!

Note: The dialogue also scales to fit, allowing shorter responses to feel more impactful by being larger!

Rule 2: NO REFERENCES!!!

Look, references are good in lots of games, they can be playful, offer a fun easter egg for those in the know, and let you highlight your artistic influences.

But for Key Fairy, one of the core things we are aiming for is a sense of Immersion in this fae world.

References only work because they detach the player from the world, which breaks the spell we are trying to weave with the game.

Note 1: This also applies to the larger game. We draw inspiration from other art and folklore, but we are trying to create a unique world, with unique monsters, stories, and people.

Note 2: While we don’t have references, characters do break the fourth wall. I have found that this doesn’t have the same effect, instead feeling more like a classic folktale flourish where the storyteller addresses the audience.

Rule Three… Choices or Less!

The dialogue system can only provide a max of three response options for players.

This is partially to stop decision paralysis for players, but also partially to make my life easier.

As was said above, though, the dialogue choices don’t need to lead to different outcomes, they are often just an opportunity for player expression.

You are a participant in performing the narrative.

Note: Similar to the monster Dialogue, the players responses have a limited character count, forcing me to write concise responses!

Rule 4: No Names!

There are unique characters in the forest.

But they don’t have names.

Instead, they will sometimes have roles, such as “The Princess of Thorns”, or titles they are referred to as by other characters, such as “The Beast”.

We want the characters to feel a bit animalistic, like they aren’t humans, but they are still people.

We also want the world to feel a bit alien, and named characters would add too much grounding to the experience.

Note 1: This is also true of the player character. “the key fairy” is just a role, and at several points in the game you can stop being the key fairy, with a new creature taking up the cloak and needle and continuing on.

Note 2: The lack of “official” names means that characters can refer to the key fairy by a variety of different titles or nicknames (such as “traveller”, “little mouse”, “fool”, etc.). In turn, the player can refer to different creatures with various titles.

Soft Rules.

Soft Rule 1: No Jokes

While there’s obviously a lot of humour in the writing, the folk of the forest aren’t Telling Jokes. Every character is essentially setup to be the Straight Man in the comedic relationship (“straight man” is just a comedy term… none of the characters in Key Fairy are straight).

Note: The exception to this is the key fairy, who is given the options to make jokes and play tricks in classic fae fashion (they are still not straight though).

Soft Rule 2: You are not an Outsider

This is a really broad rule, but essentially:

- The fairy is lost and confused, but so is everyone else.

- The NPCs are strange and magical forest creatures, and so are you.

- You aren’t the “Hero”, you are just creature of the forest who found a needle and thread, and is currently filling the role of “Key Fairy”.

Soft Rule 3: Monsters have Types, but are still Individuals

This is a difficult line to walk.

I want the different monster types to have their own voices and vibes, to provide varied flavour to the writing.

The moss-trolls ask bizarre esoteric questions, the ooze-witches are derisive and conspiratorial, the gnomes just make strange gabbling sounds.

But I also want it to feel like there is variation within the monsters.

Maybe you come across a witch who’s fallen in love with a slime, or a lost and lonely gardener in the Thicket, or a knight who dreams of being a key fairy.

Soft Rule 4: There are no locks in the forest, but there are Gatekeepers

There’s no separate systems for locks, gates, ladders, merchants, signposts, nodes, etc.

Everything just uses the dialogue system.

Which means that everything can be a character!

and every character should have personality.

even the gate-keepers, and the sign-posts, and the nodes.

Style

As well as limitations, there are some elements and choices that I repeat a bit to produce a unique Stylistic Voice for the writing in Key Fairy.

I’m sure I have forgotten a bunch, but a few examples include:

Silence

…

– Actions –

– you shift uncomfortably –

What?

what?

Repetition

whisper whisper whisper

Repetition Repetition

As well as repeating words, there are certain dialogue segments that get repeated in places. This is drawing a lot from a practice in spoken word folklore, that I go more into here

– speaking in the form of an action, so the player doesn’t know what is said –

– you respond, furthering the conversation –

Having a back and forth, with increasingly long sentences, followed by a short, often single word, response.

Yes.

Finishing sentences with a question mark?

Sentences?

Thus Ends our Tale

(I’m not going to explain the joke).

So that’s how I have approached the challenge of writing dialogue for our game.

It’s a lens that’s been helpful for my writing.

Clear Goals.

Strong Limitations.

Unique Style.

Thanks for reading!

Note: This is a helpful approach for me, but it is only one approach! I’m sure other people have different ways to approach games writing, maybe that lean more into plot structure or characterization? I’d love to hear them!

Note 2: There’s a bunch of stuff I couldn’t fit into here, including branching dialogue progression, in-game thought bubbles, sounds, the editing process, and the overall tone of the writing.

Final Note: I hope you are having a good day!