PART 1: User Mental Models?

“User Mental Models”* is a concept in design which describes:

How a user believes an object or system works

This is a general design term, in games we would call it “Player Mental Models”.

Essentially, when a player sits down to play a game they begin developing a map in their mind of how they believe the game works.

What are the systems? What elements are connected? How much is intentional? How much is randomised?

As they play further they will develop a more complex model, but crucially:

They will never understand the true shape of the system.

A player inside of a game is not equipped to understand how the game actually works.

It obviously depends on the player, but someone lacking experience in the technical side of game development will likely not be able to discern the true mechanics at play.

However,

The Goal is Not for the Player to have an Accurate Model!

The goal is for the player to have a Mental Model that Facilitates the Desired Play Experience!

Part 2: Usability Signals & Information

“Good Design” delivers an experience that requires as little direct explanation as possible.

For the understanding to be, essentially, subconscious.

You want the game to be discoverable, for the player to be able to develop an intuitive, personal, understanding of how the systems will react to their actions.

The intention is to ensure users are given Information that can allow them to build a mental model that isn’t necessarily accurate, but is Useful.

To do this, designers can develop in ways that Signal the Intended Play.

In the broader design world, these are called “Usability Signals“.

Let’s think about doors:

Push-to-open doors, such as those found in office buildings, are notorious for a sort of everyday embarrassment as users attempt to pull from the push side.

The classical solution has been to stick a “push to open” sign on the door.

This is bad design, not just because users shouldn’t have to read instructions to open a door, but because they won’t.

A good solution would be to remove the handle on the push side, replacing it with a push plate. When you do this you Signal how the door should be used, and you create a situation where it’s hard-to-impossible to be used incorrectly!

And this idea of Usability Signals also applies in game design.

Logic:

Many signals come from logic, as with the door example:

If the door has no handle, you have to push it.

Game worlds aren’t real, and so their logic and physics is a decision, made by the developers, and it needs to be taught to players.

When you are introduced to the gravity gun in Half-Life, you enter a room containing a zombie corpse, bisected by a saw blade.

There is a lesson here:

If a zombie is hit by a saw blade, it will cut them in half.

You can’t progress without picking a blade from the wall, and, when you do, a zombie walks into the room.

Providing a clear, consistent, and predictable set of rules to a game world helps players concoct plans, and expand their mental model of the games systems!

Part 3: Skeuomorphism & Culture

As well as in-world logic, developers can make use of players prior experience with games to bypass an amount of player teaching.

But not everyone has the same cultural understanding!

If you didn’t grow up playing video games, you won’t be working from the same logical framework.

So you need to understand your audience!

Developers, like Nintendo, that aim for broader audiences, don’t take gaming experience for granted, and so will usually teach players the logic of the world.

But they don’t have to teach you how to play Wii tennis, because they are relying on skeuomorphic design!

Skeuomorphic design is the practice of making digital elements draw design cues from other, generally older, objects or systems.

Interaction systems like those often used by VR and Wii sports are easier to understand for less experienced gamers because they are analogous to real-world interactions.

Even without that hardware, though, a game like What Remains of Edith Finch is able to present the player with a variety of different microgame vignettes, and can use skeuomorphism to avoid interrupting the player experience with excessive tutorialization.

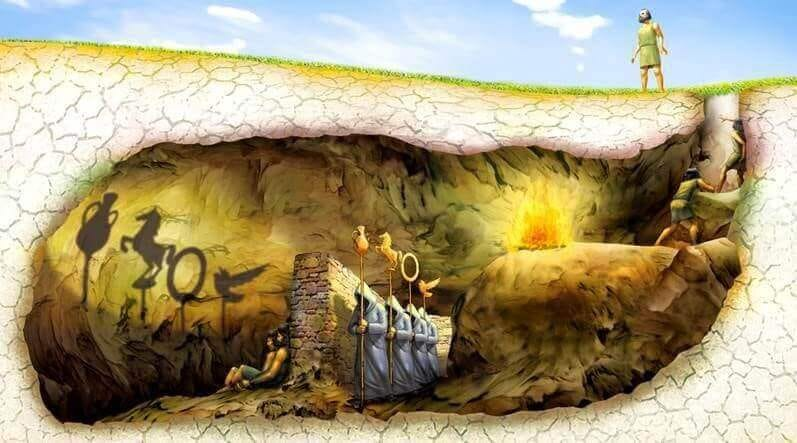

Part 4: The Descent into Darkness

Once you understand that players have Mental Models that are independent of the true shape of the system, you can start to design games in weird ways.

And so this is the part where I say something potentially controversial:

You Can Lie to Players

It doesn’t matter how the system works.

What matters is how players believe the system works.

Your system doesn’t need to be fair. AI doesn’t need to be smart. Non-fiction is fiction. What matters is the Player’s Mental Model.

Think about Resident Evil 4’s sliding difficulty scale (Here’s a video on it if you don’t know about em’), which secretly makes the game easier or harder to account for player skill.

Think about Halo’s famously intelligent AI, which is actually just designed to be really Aggressive and Tough, while actually being hyper Predictable.

And think about the Beginners Guide, which exists under a foundational lie about the entire game’s production and development.

Part 5: You should lie, all the time?

I’m not just saying you should lie all the time.

And I’m definitely not advocating for an artform built entirely on psychological tricks.

What I’m saying is that:

YOU ARE ALWAYS LYING TO PLAYERS

Game worlds aren’t real.

Game characters aren’t real.

Players have to suspend disbelief to participate in games.

And you should keep that in mind when making games!

You aren’t just developing mechanics,

You are Designing an Experience.

And that experience only exists in the Players Mind.

Note 1:

I first heard about this concept in Don Norman’s “The Design of Everyday Objects”, a foundational text in the design world, that I recommend you go read!

Note 2:

I’d also recommend people check out the episode of the incredible design podcast 99% Invisible on Norman Doors (You can find it here!)

Note 3:

Oh hey, there is research on this idea in games, especially in regards to AI programming and design. I didn’t know that when I started writing, but there you go!